Improve Recovery and Bust Stress with Box Breathing

Here at XPT, we use lots of different breathing techniques for many different purposes. Think of it as a breathwork toolbox. There is no single “right” way to deliberately control your breathing. When working on a home improvement project, you don’t want to use a hammer to cut a piece of wood or turn a screw—it’s a saw and screwdriver you’re after. Same goes with controlled, intentional breathing exercises, like box breathing.

We start with the goal or outcome you desire, see whether that involves upregulating—such as for a hard interval session—or downregulating—like at night after a stressful day—and pick the appropriate breathing pattern. The ability to tweak the knobs and move the levers with cadence, tempo, holds, and so on gives us almost an endless number of possible combinations that can get you to where you need to be physiologically or help you break out of an undesirable state.

Building a Breath Box

Some of the easiest and most effective breathwork exercises to master are box breathing techniques. What is box breathing? It has nothing to do with physical boxes, but rather refers to the breathing pattern itself.

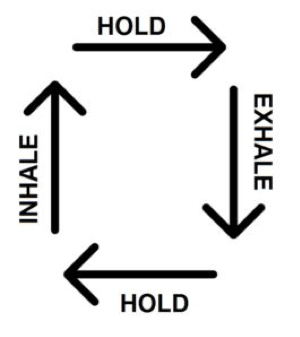

Box breathing involves giving equal time to a nasal inhale, first breath hold, nasal exhale, and second breath hold. Imagine each one being the side of—you guessed it—a box, with the duration of every phase represented by an edge (see image below). The even tempo and cadence of box breathing makes it relaxing, not least because it encourages you to focus on counting the duration of all four “sides.”

When people talk about “meditation breathing” or “mindfulness breathing,” they’re usually referring to a breath pattern that clears the mind and draws attention to one thing. Boxed breathing is perfect for this.

Nose + Diaphragm = Better Breathing

As with other calming breathwork techniques, the diaphragm should initiate box breathing – aka “belly breathing.” This large muscle, which attaches to the front of the rib cage, spine, and multiple other structures in the torso, acts like a bellows, allowing us to draw in sufficient air and then expel it again without fatiguing secondary respiratory muscles like the intercostals, lats, and so on.

When these get tired out by trying to take over the diaphragm’s natural role of the prime mover in breathing, they send fatigue signals to the brain that causes the nervous system to protect itself by reducing speed and power output. In turn, this has a limiting effect on your performance in both training and competition, and can even contribute to the dreaded “bonk” during endurance events. Until recently, it had been assumed that this phenomenon was purely due to glucose stores being used up, but more recently, the role of shallow mouth breathing has been identified as a causal factor, as well.

We often think of nutrients from broken down food being the only fuel for our muscles, when in reality, they’re also powered by oxygenated blood. If you’re not breathing in a sustainable, controlled way from your diaphragm, your soft tissues will not receive the supplies they need to keep going and do so optimally.

Nailing Box Breathing Basics

One way to practice or re-learn breath control is to do it without the added demands of load, speed, or duration that you’d be subjected to during a workout.

Enter box breathing while sitting or lying down. Closing your mouth and breathing through your nose is the simplest way to initiate diaphragmatic breathing in this or any other nasal breathing pattern. As box breathing is meant to be relaxing, try to do it in a quiet place when possible, to amplify the positive effects of the breath itself.

Once you’re situated, focus on clearing your mind, and breathing slowly and rhythmically as you follow this simple pattern:

Breathe in through your nose for four seconds

Hold your breath for four seconds

Breathe out through your nose for four seconds

Hold your breath for four seconds

Repeat for five to 10 minutes

You can do your box breathing in the morning to center yourself before the rest of your day unfolds. It can also be beneficial to complete just a few “boxes” before you give a big presentation at work, while you’re waiting in line at the post office, or when you’re stuck in traffic. It’s also an effective method for helping you to chill out and decompress in the evening.

Boosting Cognition and Enhancing Recovery

Once you’ve been box breathing for a couple of weeks and have the pattern down, you can try extending the length of each “side” of the box. Move up to five seconds and then, if you feel comfortable with it, extend to six or seven. It’s unnecessary to go any further, however.

Unlike certain apnea protocols which feature a long breath hold or the kind of max breath holding that free divers and big wave surfers like XPT co-founder Laird Hamilton undertake, the power of box breathing is not found in challenging your cardiovascular system. Rather, the value lies in its ability to focus your body and mind, groove vitality-promoting nasal breathing, and ease you into a parasympathetic recovery state.

Even with the 4-4-4-4 cadence, you’ll only be taking four breaths in just over a minute. Research points to a wide range of positive effects—benefits of box breathing that have measurable physical, mental, and performance improvements.

Australian scientists found that slow nasal breathing improves autonomic system balance and heart rate variability (HRV) coherence, which help ensure adequate recovery. Taking slow, regular nasal breaths can also benefit your brain. Chinese researchers discovered that after 10 to 12 weeks of controlled diaphragmatic breathing, participants increased their attention span and improved emotional stability.